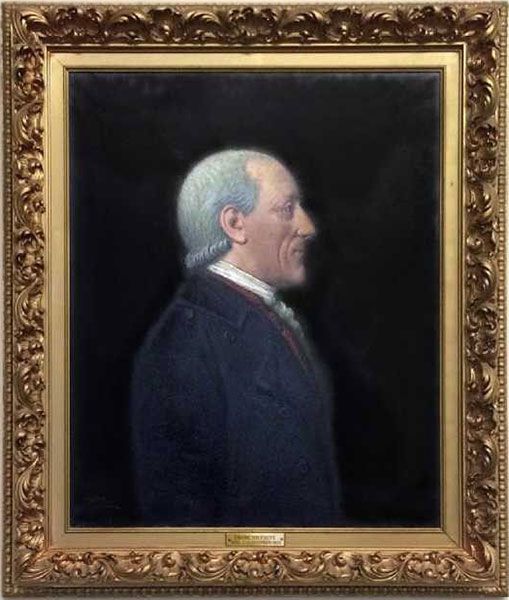

April 11, 1742 – May 29, 1789

Lt. Colonel Edward Antill was born on April 11, 1742 in Piscataway (Piscataqua), Province of New Jersey. He was the fourth of six children born to Edward Antill (1701-1770), a colonial plantation owner, attorney, and early politician in New Jersey, and Anne Morris (1706-1781). His maternal grandfather was Lewis Morris (1671-1746), Royal Governor of New Jersey, and his paternal grandfather was Edward Antill (c. 1659-1725), an English-born merchant and attorney.

Early Life

In 1762, Antill graduated from King’s College (now Columbia University) in New York City. He was admitted to the bar in New York, but shortly thereafter removed to Quebec, where he remained until the American Revolution began.

On May 4, 1767, Antill married Charlotte Riverin of Quebec City.

They had six children:

- Mary Antill (14 Jan 1771)

- Isabella Graham Antill (6 Mar 1768)

- Charlotte Antill (2 Sep 1769)

- Julia Antill (29 Mar 1772)

- Euphemia Antill (5 Jul 1773)

- Edward Antill (28 May 1775)

- Amelia Antill (15 May 1777)

- John Antill (15 Dec 1779)

- Harriet Antill (12 Sep 1780)

- Louisa Antill (2 Dec 1782)

- Frances Antill (4 May 1785)

Edward Antill and Freemasonry

It is clear that Edward Antill had been an active and ardent Freemason. In 1767, at a meeting of the Provincial Grand Lodge of Quebec in the city of Quebec, a Petition was presented by the R.W. John Collins from Edward Antill Esq. of Montreal setting forth that a Deputy Grand Master for the District of Montreal “is absolutely necessary to preside more immediately over the Lodges there.” This proposal received the unanimous approbation of the Grand Lodge and a Warrant was ordered to be made out in favor of Brother Antill and sent to him as soon as possible.” Besides St. Peter’s No. 4 there were doubtless two or more Military Lodges at Montreal during this period.

Edward Antill most likely joined St. John’s Lodge No. 2 at Fishkill while he was stationed there or in 1775 when many members of the Lodge were fighting with Montgomery outside Quebec. He is also referenced as a Past Master, although the year has never been identified. It was most likely at some point in the early 1780’s when the Lodge returned from Fish Kill to New York City and while Captain William Tapp, the Master from 1776 to the end of the War, was still stationed upstate.

In Calcott’s Disquisitions, published in 1772, he is listed as a subscriber and a resident of the Province of New York who is a Right Worshipful and Deputy Grand Master of the Province of Quebec.

Military Service

Edward had been in Canada ten years when the Revolution began, and being in Quebec in the Fall of 1775, when that city was besieged by the American troops, he refused to respond to the call of the governor of the city to take up arms in its defence; and was sent out to the American lines, and gladly assigned to duty with the 2nd Canadian Regiment (also known as the Congress’s Own) serving as chief engineer of the army, by General Montgomery. He was with that gallant officer when he fell, and was dispatched by General Wooster to relate the particulars to General Schuyler and the Continental Congress.

After the failed attack on Quebec, Antill was sent by General Wooster to the Continental Congress in Philadelphia. On January 22, 1776, he received a commission as Lieutenant-Colonel of Colonel Hazen’s Second Canadian Regiment[1], and in May, 1776, General Benedict Arnold assigned him to duty as Adjutant General of the American Army in Canada.

Congress’s Own was even then a strong regiment – seven hundred and twenty men – but Congress appears to have valued it in ordering it to be it to be recruited in any of the States to four battalions of five companies each, with four Majors and other officers in proportion.

Sixteen companies, however, appear to have been the fullest complement of what was known as

“Congress’ Own,” It had evacuated Canada, under General Sullivan, and therefore continued in his Brigade, which served with the main army at Trenton and Princeton, and later, in protecting the lines at Morristown. On the 8th of January, 1777, General Washington wrote him from his headquarters there a letter suggestive of coming action:

Call upon all your officers who are upon recruiting service to exert themselves as much as possible in filling their companies and sending their recruits forward to some general place of rendezvous, that they may be armed, equipped and got into service, with as much expedition as possible. As you and Colonel Hazien had the nomination of your own officers by virtue of your commissions, I shall have no objection to any gentleman of good character whom you may think fit to appoint,

On the 24th of February following, Richard Peters, Secretary of War, urges, in a letter, upon Colonel Antill, then commanding the regiment, the necessity, from impending events, of promptness in hurrying his companies forward to unite in meeting the enemy.

In complying, the regiment was soon actively engaged under Sullivan, and when he attacked the rear of Howe’s army on Staten Island, consisting of three thousand British and loyalists, with eight hundred men on the 22nd of June 1777, after partial success succumbed to the vigorous resistance, he became a prisoner, thereby losing his opportunity of being present at Brandywine, Germantown, and in much important service with his regiment.

He remained on a prison ship on the Hudson River for three years. Happily for him, his brother John[2], then in the British service, was one day sent to examine the condition of the prisoners, and the first person he saw among them was his own brother Edward, whose release he soon effected. He and other American officers made a return, at Flat Bush on Long Island, August 15, 1778, of the officers and other prisoners on Long Island for purposes of exchange. In August, 1779, he was still at large on Long Island, on parole.

While a paroled prisoner of war at Flat Bush, Long Island, Edward Antill wrote or copied a group of scientific papers. Subjects include “The principles of geology and astronomy,” “Elements of chronology,” “Elements of all the syllables within the English language,” “A table of the sun’s declination from 1764 to 1795,” and a table showing the number of miles to each degree of longitude and latitude.

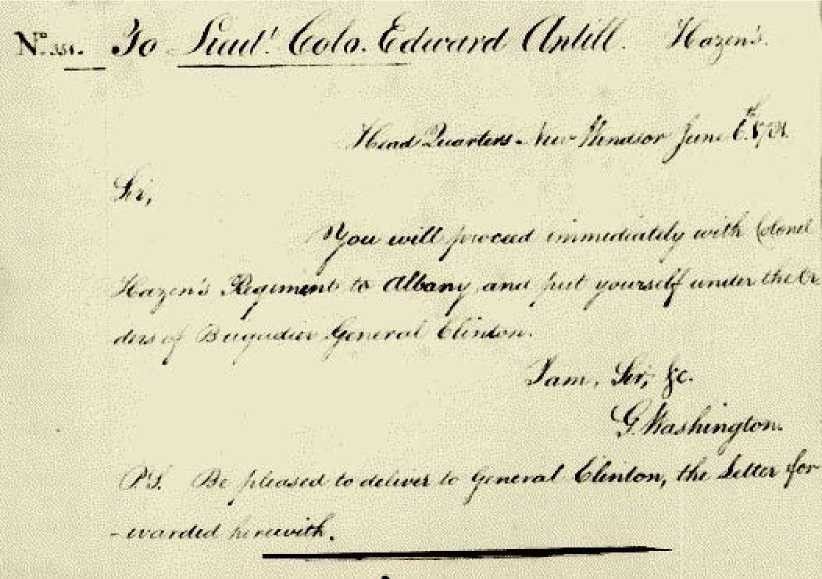

His exchange was effected Nov. 2, 1780. In a letter from General George Washington, he is ordered to meet up with Hazen’s Regiment:

Sir, Head Quarters New Windsor June 1st 1781

You will proceed immediately with Colonel Hazen’s Regiment to Albany and put yourself under the orders of Brigadier General Clinton.

I am, Sir, etc.

G. Washington

P.S. Be pleased to deliver to General Clinton, the letter forwarded herewith.

Letter from George Washington to Edward Antill

Upon his release, he followed and rejoined the 2nd Canadian Regiment re-joining them at Fishkill, NY, and soon afterwards assisted in routing the quarters of Colonel James de Lancey at Morrisania, for which he earned the thanks of Washington in general orders.

In August he marched to Philadelphia, joining Colonel Olney’s Rhode Islanders, and proceeding by the Chesapeake and James River to Yorktown and the surrender of Cornwallis. At the Battle of Yorktown, Edward Antill and Alexander Hamilton each led regiments under General Moses Hazen, leading to a friendship between the men. After the war, Antill’s daughter Mary married a young New Yorker who had led one of the charges at Yorktown under Hamilton, Gerrit G. Lansing.

On Jan. 7, 1782, he returned 77 men of his regiment belonging to the Pennsylvania line, who had not received the gratuity allowed them.

Although he had asked Congress to be relieved from service in an earlier period of inactivity, he continued therein until the disbanding of his regiment in November, 1783.

Not found on the Half-Pay Roll, he appears on the Balloting Book of New York in the list of Canadian and Nova Scotia refugees, who had united with the Americans, to whom lands were granted by the State under the direction of its commissioners.

He was retired from the service on January 1, 1783. He subscribed his name to the Institution of the Society of the Cincinnati with the officers of his regiment on the Parchment Roll, with Washington at its head, now in the possession of the General Society.

Post Military

He was licensed as an attorney in New Jersey at the November Term in 1783. About this time, he opened a law office in New York City at No. 25 Water Street and later moved to No. 87 Broadway at the corner of Wall Street. In a letter dated “31 Golden Hill, New York City,” December 16, 1785, he applied to John Jay, then Secretary for Foreign Affairs, to be appointed Translator in the Department of Foreign Affairs. Secretary Jay replied with his compliments that the office was not vacant.

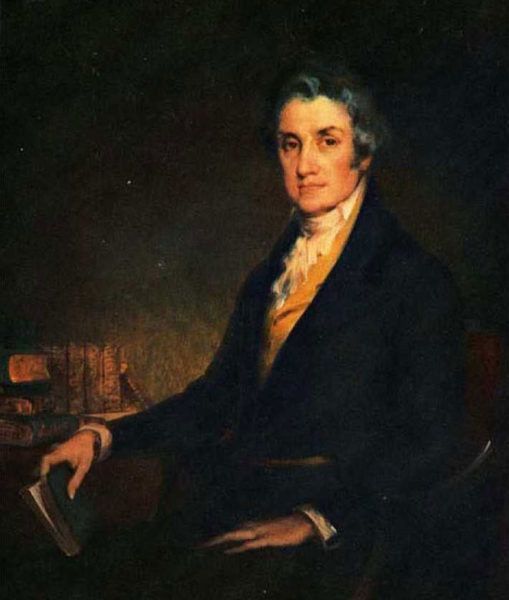

After the Revolutionary War, Antill soon fell upon hard times, and he suffered a breakdown after the death of his wife Charlotte in 1785. In 1787, he left his youngest child, two-year-old Frances (Fanny) Antill, in the care of Alexander Hamilton (who was then a lawyer in New York City) and his wife Elizabeth. The below is from the famed biography of Alexander Hamilton by John Church Hamilton in 1879:

Colonel Antil [sic] of the Canadian Corps, a friend of General Hazen, retired penniless from the service—his military claims, a sole dependence, being unsatisfied. Hoping to derive subsistence from the culture of a small clearing in the forest, he retired to the wilds of Hazenburgh. His hopes were baffled, and in his distress he applied to Hamilton for relief. His calamities were soon after embittered by the loss of his wife, leaving infant children. With one of these Antil visited New York, to solicit the aid of the Cincinnati, and there sank under the weight of his sorrows. Hamilton immediately took the little orphan home, who was nurtured with his own children…

Death

He joined his brother John two years later and on May 23, 1789, Antill died in Canada at Saint-Jean, on the Richeliue River, near Montreal. He was appointed Judge of the Court of Common Pleas of Clinton County, New York, in 1789, but probably died before he could fill the office.

Fanny continued to live with the Hamiltons for another eight years, until she was twelve, at which time her older sister Mary was married and able to take Fanny into her own home. Later, James Alexander Hamilton would write that Fanny “was educated and treated in all respects as (the Hamiltons’) own daughter.” She later married Arthur Tappan, a prosperous merchant and abolitionist.

Antill served with Alexander Hamilton in Hazen’s Brigade and Hamilton’s wife, Elizabeth Schuyler Hamilton, served as godmother to Antill’s daughter Harriet.

John Antill served as a Major in the British Army. He was also a Freemason and listed as a Worshipful and Grand Deacon in New York in 1772, but the Lodge is unidentified.